18 December 2019

Defrauded! The reality of Ponzi and pyramid schemes in South Africa

South Africa is, sadly, no stranger to scams. Fraudsters have taken billions from local people, not caring if they rip off the poor or elderly. J Arthur Brown stole around R1.5 billion in pensioners’ money in the Fidentia scandal. Then there is the eye-bleeding fraud allegedly perpetrated by Barry Tannenbaum: R12.5 billion disappeared from people’s wallets before he was done.

Massive Ponzi and pyramid schemes still happen today. In June, a Durban couple appeared in court for a R1 billion scheme and, just a month later, a Johannesburg businessman was arrested for his R100-million Ponzi scheme. Fraudsters have corrupted even technology – experts warn against WhatsApp Stokvel groups that are flourishing of late. Most of these are pyramid schemes.

“People behind Ponzi schemes are generally sociopaths. They are exceptionally good at getting people to part with their money. There is a reason we call these people con artists – they are CONfident and they are CONvincing.”

Chad Thomas, CEO of IRS Forensic Investigations

The face of personal fraud

A special corner of hell should be reserved to the people who will rip off anyone – especially the poor. It would be easy to blame the victims, to say they should have known better. After all, these schemes usually make promises they could never realistically meet. But this logic underestimates the type of people who perpetrate such frauds.

“I really dislike it when victims are referred to as being greedy. It is almost as if we are revictimising the victims,” said Chad Thomas, CEO of IRS Forensic Investigations. “People behind Ponzi schemes are generally sociopaths. They are exceptionally good at getting people to part with their money. There is a reason we call these people con artists – they are CONfident and they are CONvincing.”

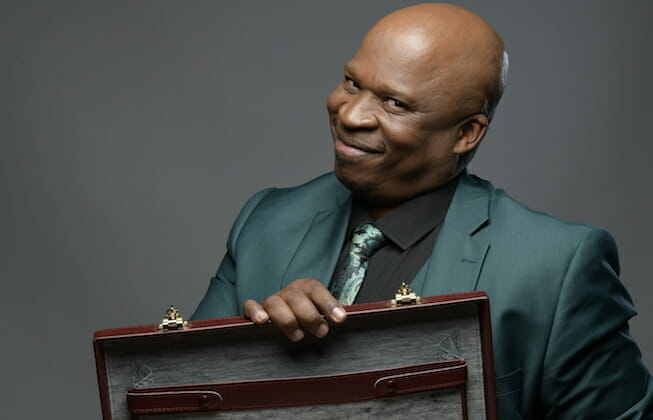

A perfect example is Khulubuse, played by the cherub-faced Desmond Dube in the Mzansi Magic drama, now streaming on Showmax, Impilo: The Scam. Dressed in a fancy suit, he charms his way into people’s lives and pockets. His estranged wife, Nokulunga (Sthandiwe Kgoroge), knows better – even when he arrived on her doorstep with groceries. Her neighbour croons over his BMW, but Nokulunga warns: “He probably stole it.”

One would expect a scam artist to show up in rich suburbs, not the dusty back streets of a township. But greed and desperation are these fraudsters’ main levers, and they often target the most desperate people.

“I think greed is a big motivator,” said Lyndwill Clarke, Head of Department: Consumer Education at the Financial Sector Conduct Authority. “But we also have high levels of indebtedness and poverty in the country. In some cases, people knowingly go into these schemes hoping to ‘get out’ early and have enough money to cover or ease their debt or to put food on the table.”

Nokulunga knows better, but her son and Impilo’s main character, 18-year old Mnqobi (Sipho Mdingo), sees his dad’s re-emergence as a chance to escape poverty. Khulubuse wastes no time exploiting his son, setting the teen down a road that soon threatens his life and freedom. Like any fraudster, he shows no remorse.

The DNA of a scam

Ponzi and pyramid schemes are the most common forms of fraud affecting everyday people. They differ in some ways, but both operate on the principle of borrowing from Peter to pay Paul.

In such a scam, a victim is promised great returns generated from a smart financial scheme. In reality, there is no scheme – the fraudsters simply use money paid by new victims to repay the other victims. They often then convince the newly paid investors to reinvest, who do so readily because they seem to have made a lot of money quickly. But there is no money being generated: once the scheme can’t attract fresh funds, it collapses, and the fraudster tends to disappear.

A Ponzi scheme is an investment scheme. It promises great returns for invested money and doesn’t seem different from other investment services. But there is no investment happening.

A pyramid scheme is a recruitment scheme. It promises great returns if more people are recruited to the scheme. This approach is often compared to a multi-level marketing (MLM) scheme, except an MLM involves selling products of some sort. MLMs are controversial, and some are considered pyramid schemes. But outright criminal pyramid schemes sell nothing but lies.

It’s perhaps best to not get hung up on what they’re called, since these schemes evolve all the time. Recent ones used promises involving cryptocurrencies and forex trading – the notorious MMM scheme defrauded 5 million people across the globe through its websites.

Some explicitly target community ties, said Thomas:

“South Africa is seeing a rise in what we term ‘affinity schemes’. This is an extension of a Ponzi scheme where the perpetrator is someone from your community or a member of the same religious organisation as you. We have seen this in the international Bernie Madoff case, as well as the local cases involving Barry Tannenbaum and Michael Ash schemes, where many of the victims came from the same community as those operating the scheme. We are also seeing a definite rise in cases involving Christian churches that preach from the basis of ‘prosperity,’ where church members, elders and even pastors have taken advantage of congregants.”

Don’t get caught

In Impilo, Mnqobi is manipulated by his father to be the face of the scam, taking money from desperate community members. Perhaps we can be forgiving of this young man, who had to choose between grinding poverty and the promises of an absentee dad.

But it’s nonetheless astounding that so many continue to fall for these schemes. Spotting them is not very difficult. An offer that seems too good to be true often is, and you should interrogate the offer carefully, said Clarke:

“Ask these questions: How long have you been in the investment business? What are your qualifications? Do you require me to introduce other investors? Are you authorised by the Financial Sector Conduct Authority [FSCA] to sell this product or service? Can you show me proof of your company registration and authorisation from the FSCA? What product am I investing in? Will I receive signed documentation?”

Be careful of fake documentation. It’s always smart to contact the FSCA (0800 20 37 22 or info@fsca.co.za) and check if the person and their company are legitimate. If you suspect fraud, the FCSA hotline is 0860 101 248.

It might be too late for Mnqobi. Things don’t take long to unravel in Impilo, especially as his father’s past comes back for him and the scheme’s victims realise they were robbed. But this is the reality for countless South Africans every day.

How to spot a fraud

Fraudulent schemes can appear in many different forms. Con artists are clever, so they evolve new ways to fool people. But there are a few rules of thumb that you can apply. Don’t be afraid to ask questions and demand answers. If it doesn’t add up, walk away.

The warning signs of such a scheme include:

- Claims of big returns quickly with little risk.

- Asking you to recruit more investors to boost your profit.

- Pay-outs are made from new investors, not from profits.

- People at recruitment meetings who testify about their great returns.

- The scheme is invitation only or “unique”.

- You are being pressured to make a deposit quickly.

- The scheme’s representatives aren’t registered with the Financial Sector Conduct Authority (FSCA).

- Representatives don’t like specific questions about the offer or how they generate profit.

The dodgiest dealings on TV

If real life is getting you down, enjoy the antics of the dodgiest businesspeople on TV. In The River, Cobra has shown he’s not above corruption, taking back-handers to secure tenders. Dambisa was also recently in hot water when it emerged she’s spent the family’s stokvel savings on a brand-new car. And of course, the arch-villain is Lindiwe, who will go as far as murder to get what she wants.

Not all the drama on The Herd was supernatural, either – the trouble caused by Smangaliso Mthethwa was entirely man-made. He scammed farmers so he could pocket their money – but he gets his comeuppance in the end.

And of course, scams aren’t unique to South Africa. Watch HBO’s Billions, the highly acclaimed HBO show about a hedge fund manager whose corruption sets a tenacious US attorney on his tail. Or binge both addictive seasons of HBO’s Succession, where mega-wealthy heirs to a media empire fight it out for control. They’ll stoop to any depths to stake their claim.

The Roast of Minnie Dlamini: The roast everyone's been waiting on

Empini, coming soon

More Mzansi gold

Your initiation into the cool, chaotic world of Wyfie

Feel like we’re almost at midterms but you stopped going to class after you skipped a couple of lectures? Let’s swot up on Episodes 1-24 of Showmax Original Wyfie.

Must-watch trailer for The Showmax Roast of Minnie Dlamini

See the trailer for The Showmax Roast of Minnie Dlamini, premiering on Showmax this Friday, 26 April 2024.

Nambitha Ben-Mazwi stars in Showmax Original Empini

Multi-award winner Nambitha Ben-Mazwi leads new Showmax Original Empini. The action-packed drama series premieres on Showmax 23 May 2024.

Youngins Season 1 episodes 31-33 recap: Revelations

Amo and Mahlatse become a couple, Tumelo ditches Sefako, and Khaya sees both Sefako and Principal Mthembu in a new light in episodes 31-33 of Showmax Original Youngins.